Where do stories come from? Before I wrote The Mermaid Game: A summer short story, I wrote this short nonfiction essay about a long-ago beach and summer. This telling is as true as my faulty memory can make it. Read this summer memoir with The Mermaid Game to see where the story and essay converge and diverge to create the different kind of truth that can be found in fiction.

A summer memoir by Kell Andrews

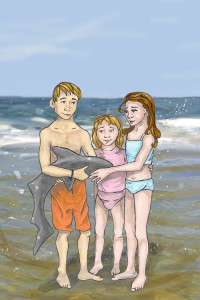

Illustration from The Mermaid Game: A summer short story

Get Kindle edition

Stone Harbor, New Jersey, is a fancy beach town now, but it wasn’t when I was a kid – at least not where my grandfather’s house was. The beach house was really a shack. We called it the Minnow – a little red house, three tiny rooms in a shotgun layout, plus a screened-porch and a bathroom with a shower where the water drained through screens into the stones outside. Once it had been crew quarters for the old Coast Guard station across the street.

When my grandfather bought the Minnow, it was the second house from the beach on the third-to-last street on the island. By the time we came along, another block of big houses had sprouted between the beach and us. A few years later, another five streets were carved out of the scrubby beach preserve that stretched to a point into the bay. The forces of development that turned dunes into houses were as inevitable as tides.

But at this time, Stone Harbor was poky – a barrier island, the buffer between the ocean and the mainland. My family spent a week or two each summer, and when we were in town, usually Jackie was too. He was my sister Kim’s age, staying with his own grandmother and grateful for a group of kids down the block, even if we were girls.

My mother had taught us how to build castles, mining deep in the wet packed sand to create a well. We built up our walls, keeps, and turrets drip by drip. It was Jackie who taught us to make a base of jagged shells so that if anybody jumped on it, they’d get a lesson not to repeat the sacrilege. I hoped nobody tried it.

We swam, jumped over waves, and, one summer in particular, we watched for sharks.

The movie Jaws had come out, and we didn’t need to see the R-rated movie to know what it was about. Floating on a raft, legs dangling, we imagined sharks beneath us – prehistoric predators with rows of teeth to tug us beneath the waves and swallow us in great bloody chunks.

A few times that year the lifeguards whistled everyone out of the water, fearful that they had seen a fin. It could have been a dolphin, a bluefish, or their own imagination – we were taking no chances. It didn’t matter that there hadn’t been a deadly shark attack at the Jersey Shore since 1906. Some truths you feel in the cold of your bones and the crawl of your skin, not in your head.

So we watched the waves, scanning for fins. We had a lot of time to do it – back then you had to wait a half-hour after eating before swimming – everyone knew that otherwise you might get a cramp and drown.

I expected to see a shark out in the deep, not in the shallows. The little shark didn’t look fearsome. It struggled in the current, even the gentle low-tide surf. We ran up to it, falling back when a wave rolled it towards us. It flopped on the sand, three feet long. Its round eye looked dead and dull as a lead coin. We ventured closer. Its mouth had an underbite, a slash as wide as hand lined with jagged teeth. Then Jackie picked it up, one hand below its dangerous mouth and the other behind its tail.

He posed, triumphant. A shark hunter. He hefted it, flexing its body.

I didn’t want to touch it.

Then I saw its gills flutter weakly. It was alive.

“Not for long,” Jackie said, cackling. The shark was dying.

And what could I do about it? I called my mother.

Jackie showed off the shark proudly.

“Throw it back,” my mother said. “It’s a sand shark. It’s harmless.”

He stared at her, dead-eyed as the shark. Then he swung the animal and hefted it into the waves, where it was drawn into the boil of water. Then the wave receded and we saw it again, a fin and a tail, sand-colored, nearly invisible in the gray-green Atlantic waters.

What then? We were at the beach and there was a shark swimming right off shore.

We packed up and left, my mother, sisters, and I. Jackie stayed behind.

Later that afternoon Jackie came by the Minnow triumphant once more. He held the shark by the tail.

Now it was well and truly dead.

“Let’s cut it open and see what’s in its stomach,” he said.

I thought its eye dead before. Now I realized I had been wrong. This was what dead really looked like.

We laid it on a paper bag, and this time I touched the shark’s skin — rough like sandpaper made from ground glass. Jackie sliced open its belly with a kitchen knife, and the clean salty smell was enveloped in a miasma, foul and fishy and rotten. The entrails spilled out. He poked through it. Except for one silvery minnow, it was a muddle. We couldn’t tell what was the shark and what it had eaten.

We bundled up the mess in the sopping bag – garbage, not a trophy any longer.

It was a short walk to the bay, since just two blocks separated the inlet from beach at our end of the island. We emptied the bag of entrails over the sea wall. Some of the guts floated to the surface, pink, gray, red and livid.

The next day I still watched the waves for fins. Some monsters are real, and some stories are true. But the cold had gone from my bones, and I wasn’t scared anymore.

About the author: Kell Andrews is always on the lookout for treasures and discoveries in woods, parks, cities, and beaches. Kell is the author of Deadwood, a middle-grade novel from Spencer Hill Press, and Mira Tells the Future, a picture book upcoming from Sterling Children’s.

Pingback: Stories found and made: The difference between fact and fiction - Kell Andrews, writerKell Andrews, writer