Writing a sequel is both harder and easier than starting with a blank page. You already have characters and a world — but how do you make it all hang together?

When I wrote Deadwood, it was a standalone. The story was resolved at the end, and I didn’t see how it could continue. Some readers asked if there would be a sequel, and the answer was no.

When I wrote Deadwood, it was a standalone. The story was resolved at the end, and I didn’t see how it could continue. Some readers asked if there would be a sequel, and the answer was no.

Then I found another story for Martin and Hannah. I had other projects before it came to the surface, and it simmered for a long time (nearly burning dry and setting off the fire alarm along the way). But now, with Deadwood out in the world, my thoughts have turned back to the world of Deadwood and my 12-year-old characters. I want to be in their heads again, and at last my Deadwood sequel is turning into work in progress. and not just another item on my story-ideas list.

It’s a new mystery, not a part two, a duology, a trilogy, or a series. It’s fun to be in the world of Deadwood again, and so familiar seeing it through the eyes of Martin and Hannah. But I’m finding a new set of challenges.

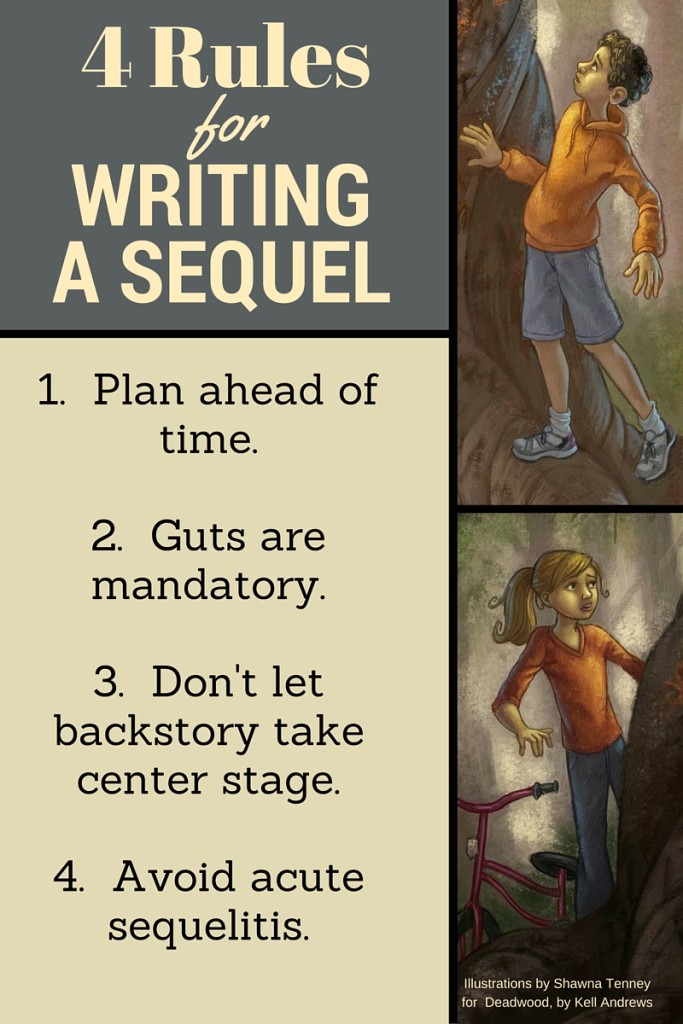

I went looking for some sequel wisdom, and here are four rules I found.

1. “Plan ahead of time.”

Miss Literati – How to Write a Sequel the Right Way – “Though some can get away with creating a sequel at the last-minute, it may be a better idea to plan ahead of time.” Oh well. Too late for that. Hopefully I can keep my threads straight.

2. “Guts are mandatory.”

Caragh M. O’Brien, Writing the Second Book: Not Any Easier – Caragh O’Brien, author of the brilliant Birthmarked trilogy and upcoming The Vault of Dreamers, didn’t started planning her trilogy while editing book one, so she was able to avoid writing into a box — but she still had a lot of work to do in creating new challenges for book two. Guts were mandatory for everyone too: “In fact, my earliest draft was such a mess that it frightened my editor, Nancy Mercado.” The published book, however, improved on the first.

3. Don’t let “back story and infodumping take center stage.”

Lydia Sharp, On Writing Sequels – Lydia Sharp (Twin Sense) talks about writing and reading sequels — specifically, the sssue of backstory and infodumping. How much do you need? How do you remind both readers of the first of what has happened without beating them over the head? I’ve decided that while drafting, I’ll backstory and infodump my heart out. I’ll include it all now, then edit out what isn’t necessary. Easier to delete some things than not write them at all…

4. “Don’t let acute sequelitis happen to you.”

Nathan Bransford, former agent and middle-grade author of the Jacob Wonderbar books, says that Acute sequelitis means being too attached to your characters and world so that you write a sequel to a book when no oide dreams of a massively long series when the first book in the series doesn’t work out.”

As a writer approaching release of my first book, point number four is a little touchy, so I’m going back to number two — Caragh’s advice. Now that I think about it, I’m one for four on this list.

Guts may be mandatory, but nothing else in writing is.

From reading or writing sequels, what advice do you have? I could use it…

Adapted from a post originally published on Operation Awesome.