This post appeared as part of Middle Grade Month on Diversity in YA, a blog founded by YA authors Malinda Lo and Cindy Pon in 2011 to support diverse literature.

Deadwood, my middle-grade mystery, takes place in a diverse town, like communities I based it on and where I’ve always lived. Culture is not central to the story, which is about two seventh graders who must lift a curse on a tree to save their town from growing disaster, but I wanted to include diverse characters to reflect the reality I pictured.

Still, I was intimidated about writing someone from another culture, so I decided to hedge a little. When I began the novel, the main character of Martin had a Puerto Rican dad but was raised by his white mother and grandmother. I thought if he was raised in my own culture, I had the right to write him.

The story is not about the ethnic background, and it’s been said that Martin “just happens to be” Puerto Rican. But it didn’t just happen to him, just as my other main character, Hannah, doesn’t “just happen to be” white. I decided that these would be the characters, and I grew their voices, personalities, and backgrounds. It didn’t just happen.

As I wrote the story, my understanding of the character changed. Although Martin’s ethnic background isn’t central to the progression of the plot, I realized it IS central to Martin himself. He asserted himself and his identity as I wrote, so I changed his heritage to fit. His mother, grandmother, and aunt became Puerto Rican too, and that changed the threads of the story and his character. Martin holds his cultural identity very close, reflective of his feelings for his mother and abuelita.

There’s no such thing as culturally generic books, but we need them.

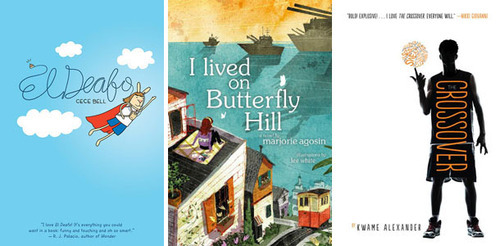

On May 1, 2014 right as #weneeddiversebooks was officially kicking off, SLJ published a list of Culturally Diverse Books Selected by SLJ’s Review Editors. SLJ wrote, “These books are those in which the main character(s) ‘just happen’ to be a member of a non-white, non-mainstream cultural group. These stories, rather than informing readers about individual cultures, emphasize cultural common ground.”

While culturally generic is not a term I love, it is established in literacy and education. Rudine Sims Bishop coined the term as part of a framework of multicultural literature for librarians and educators in Shadow and Substance: Afro-American Experience in Contemporary Children’s Literature (NCTE, 1982). The now-ubiquitious metphor of “windows and mirrors” is hers. She defined the categories of “culturally specific” — containing details that define the characters as members of a particular cultural group and “culturally generic” — representing a specific cultural group, but with little culturally specific information. (Companion Website for Elementary Children’s Literature: The Basics for Teachers and Parents, 2/e , Nancy A. Anderson)

But is The Thing About Luck by Cynthia Kadohata or Yaqui Delgado Wants to Kick Your Ass by Meg Medina — two of SLJ’s listed titles — really culturally generic? Could these stories happen to any child, of any race? I don’t think so. If you put Summer in Medina’s book and Piddy in Kadohata’s, the stories would not be the same. Summer and Piddy don’t “just happen to be” Japanese-American or Puerto Rican — it’s an essential part of their identity and the story. Good stories and characters are always specific.

But yes, as the “culturally generic” label indicates, these stories are supremely relatable for young readers. Readers of all kinds need diverse books because they are not windows or mirrors, but both at the same time. As KT Horning wrote in response to the SLJ list, characters by Kwame Alexander and Varian Johnson are viewed as culturally generic because they are writing from the inside: “more Us than Other. They have invited readers to stand on their own bit of cultural common ground for a while.”

Much of the time, culture is the framework we live inside — we don’t always see it, but it doesn’t “just happen” to characters of color — or to white characters either. White is the default in the United States. It is almost always seen as culturally generic, but it isn’t. It’s the culture that many writers write and readers read within seeing it because it’s ground they’re standing on.

“Culturally generic” books — as problematic as the term is — do the same. They are the fantasies, mysteries, romances, coming of age, and science fiction books where readers can see diverse characters like and unlike themselves doing more than explore culture. They expand the cultural common ground.

I wrote Martin as a skinny, wild-haired, Puerto Rican kid and Hannah as a tall, blonde, white one. Neither is culturally generic. Diversity in children’s books requires a decision by writers, readers, publishers, booksellers, and librarians to create and share books on that expanded common ground. Whether writers and readers experience diverse characters or only a homogenous world, it doesn’t “just happen.” It’s a decision.