Today I’m posted as part of a blog party hosted by the wonderful Eileen Manes, a picture book writer who blogs at Pickle Corn Jam. Ten of us are writing about one of our favorite books of the year — here’s mine! At the bottom the post, you’ll find links to the other blogs.

One of my favorite books when my children were small was City Animals by Simms Taback. I had always wondered about early childhood’s obsession with farms. Why is it necessary for babies to know that cows moo and pigs oink? Most of them won’t encounter these animals in everyday life. Why is this somewhat anachronistic knowledge is among the very first things we impart?

That’s why I loved Taback’s lift-the-flap book. After three clues, these animals revealed itself. I’m a PIGEON! I’m a SQUIRREL! I’m a MOUSE! These were the animals that my inner-ring-suburban children were likely to encounter (they encountered the mice with far more delight than I did).

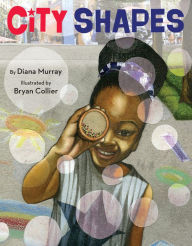

This year’s City Shapes, written by Diana Murray and illustrated by Bryan Collier (Little, Brown. June 2016) does the same reimagining to the classic shape book that Taback did for animals, and it elevates it. Shapes can be well, two-dimensional, but this book is anything but.

The young girl in City Shapes encounters CIRCLES, SQUARES, and TRIANGLES in her own city neighborhood in Murray’s flawless rhyme and Collier’s gorgeous realistic watercolor and collage illustrations. These shapes move and live, and these words are vivid and playful.

I love the specificity and sense of place here, I’d like to see similar journeys in more diverse, real places with other children.

But in the meantime, there’s even a pigeon!

“the pigeon flies back through the night cityscape/as city lights sparkle, SHAPE after SHAPE./But her heart starts to ache for the SHAPE/she loves best./The SHAPE that is home—/her warm CIRCLE nest….”

And now for the other writers and their picks for favorite children’s books in 2016:

Ready for the rest of our 2016 recommendations? Just follow the links!