I was featured as the Author Spotlight on Kidlit411 on July 1. Here’s the Q&A. You can read the full post at Kidlit411.

I was featured as the Author Spotlight on Kidlit411 on July 1. Here’s the Q&A. You can read the full post at Kidlit411.

I was featured as the Author Spotlight on Kidlit411 on July 1. Here’s the Q&A. You can read the full post at Kidlit411.

I was featured as the Author Spotlight on Kidlit411 on July 1. Here’s the Q&A. You can read the full post at Kidlit411.

I’m a Belmartian by marriage, which means I claim the beach town of Belmar, NJ, as a home. During Superstorm Sandy, Belmar’s boardwalk was destroyed, and many homes were damaged or demolished.

My beach town was on my mind when I was looking for a picture book idea, and it combined with a line from a Bruce Springsteen song, “Asbury Park, Fourth of July (Sandy).” “Did you hear the cops finally busted Madam Marie for tellin’ fortunes better than they do.”

Sandy, storms, boardwalks, fortune tellers — they all came together in Mira Forecasts the Future, the story of the daughter of a boardwalk fortune teller who can’t see the future with magic, so she learns to predict the weather with science.

Mira learns about weather, and this book is the story of a girl who saves a surfing contest and the day. It doesn’t take place in the present or in the past, despite Lissy Marlin’s gorgeous Boardwalk Empire inspired ilIustrations, but somewhere in between.

It doesn’t take place in New Jersey — it could be Coney Island, Santa Cruz, or any beach town. Boardwalks and beach towns seem like tourist traps to those visiting, but there are real people who live there. I wanted to capture a warm small-town environment — flavored with salt water taffy and pizza by the slice, soundtracked by calliope music and the crash of waves.

I write for children of all ages. Two years ago, when my first middle-grade novel, Deadwood, was released, I wrote a post called what What Writing Picture Books Taught Me About Middle-Grade Novels.

This month, my first picture book, Mira Forecasts the Future (illustrated by Lissy Marlin), hit the shelves. So now I take a look in opposite direction to assess what writing novels taught me about writing picture books.

When beginning to write picture books for young children, many writers have a tendency to want to model good behaviors. But good behaviors don’t make good stories.

Writing and reading novels prove that flawed characters are interesting characters. They make mistakes. They grow. They don’t have to be good influences.

Sometimes picture book readers — agents, teachers, parents, even kids — will call out characters for the wrong things they do, feel, or are. But the interesting, imperfect characters get your attention, and it’s the interesting, imperfect characters who have room to grow. That leads me to my next point.

In my favorite books, every character wants something. Every character has their own story and growth. Even villains are the heroes of their own stories.

In a novel, there’s plenty of room to infuse each character with their own motivations, narrative, and character arc. This deepens the emotional impact of the plot and characterization, even if minor characters do much of their growing behind the scenes.

There’s not as much room in a picture book, but there also aren’t many characters. If you can make every character vibrate with their own motivations and change in the course of the story, your picture book will pack more resonance into 300 to 800 words.

One of the biggest temptations when writing a novel — especially a big, juicy fantasy or historical — is to put all the worldbuilding and research on the page — addendums, family trees, glossaries, maps, footnotes with the history of the centuries. Sometimes this works. Sometimes it’s just an info dump.

When writing novels, you make a critical decision about what backstory not to include. Just because you know something doesn’t mean your reader needs to — the hidden history of your world makes the story more real even if you never put it in the foreground. That’s why it’s called backstory — you can’t show perspective and dimension unless there’s something in the background.

Of course, the few hundred words of text in a picture book don’t allow foreground backstory. The lesson from novels is to know the backstory even if you don’t tell it. If you understand your characters outside of those 300 to 800 words, if they live for you as people (or bunnies or sentient shovels), you’ll have a richer story.

One reason novel writers leave out backstory is that they trust their readers to pick up allusions and make connections. But can you do that when writing for very young children?

Yes. Your child readers may have only few years behind them, but they’ve accomplished hugely impressive cognitive growth before listening to or reading your story. They understand more than you think they do, and they are capable of understanding so much more than that if you give them a chance. So give them a chance.

Writing a novel takes stamina. Even a short middle grade novel is 30,000 words. Adult novels are 80,000 and more, and don’t even think about the number of words in a multibook series. You have to write a lot of words, many days in a row or over the course of months or years until you reach the end. Then you revise, again and again. It’s a long haul.

A picture book is shorter than 1000 words, the amount many writers strive to draft in a single day. A picture book manuscript often doesn’t take long to write compared to a novel. But it’s still a long haul.

The individual manuscripts may be short, but shorter isn’t easier. Every word counts. You’ll probably rewrite each one. You may start from a blank page sometimes. You’ll workshop. Revise again.

And still, that first book you write probably won’t be published. Probably not the second. Maybe even your 10th manucript still won’t interest an agent. Maybe it will take your 15th or 20th to get published. And then maybe you’ll write 10 more before you get published again.

Picture books may be short, but they’re not a short cut. Every road in the writing business is a long one. Shorter isn’t easier. Younger isn’t lesser.

Writing is hard for every age. When it works, the writer finds the story, and the story finds the reader. And novel or picture book, that’s what makes it worthwhile.

When I was a kid I loved making paper fortune tellers. I wrote the fortunes. I folded and colored the paper myself. I tried to use a paper device I made myself to predict the future.

My children do the same thing now. They know, as I did, that the fortunes you write yourself aren’t real clairvoyance. But the fortunes you write do give hints about what is possible — what you wish and fear.

That’s one of the reasons I wrote Mira Forecasts the Future. To make a dream come true, you have to think about it and work toward it. You have to make it happen.

But first you have to dream it. You have to believe it — and you have to know it’s possible for you.

Read the rest of the post at Reviews Coming at YA >>

My winter vacation comes to an end, and with it the end of a binge — not the usual holiday eating indulgence (although plenty of Christmas cookies were involved) but of a lengthy reading binge spent immersed in Regency romance. I started with Austen, went deep into the Georgette Heyer catalog, then branched out into modern writers, then back to Austen.

| The holiday binge is over. |

As after most binges, I’ve ended feeling slightly overindulged — I’ve had enough younger brothers with gambling problems, dukes with rakish reputations, and haute ton society gatekeepers to last me another six months. I also have completed a crash course in rule-bound historical romantic tension, which is just what I need for the YA historical fantasy I’m writing.

Prolonged reading binges are how I became literate in the fantasy genre and in the middle-grade category. Until those self-directed educations, I read primarily adult literary fiction, and I haven’t gone back yet. Deep and wide immersive reading is form of research for fiction writers, and for me a purely pleasurable one. I had to know the voice and rhythms before I could find my own. I needed to learn the tropes and conventions so that I could avoid or deploy them purposefully, rather than falling into them inadvertently.

I spent the day cleaning the house. This one:

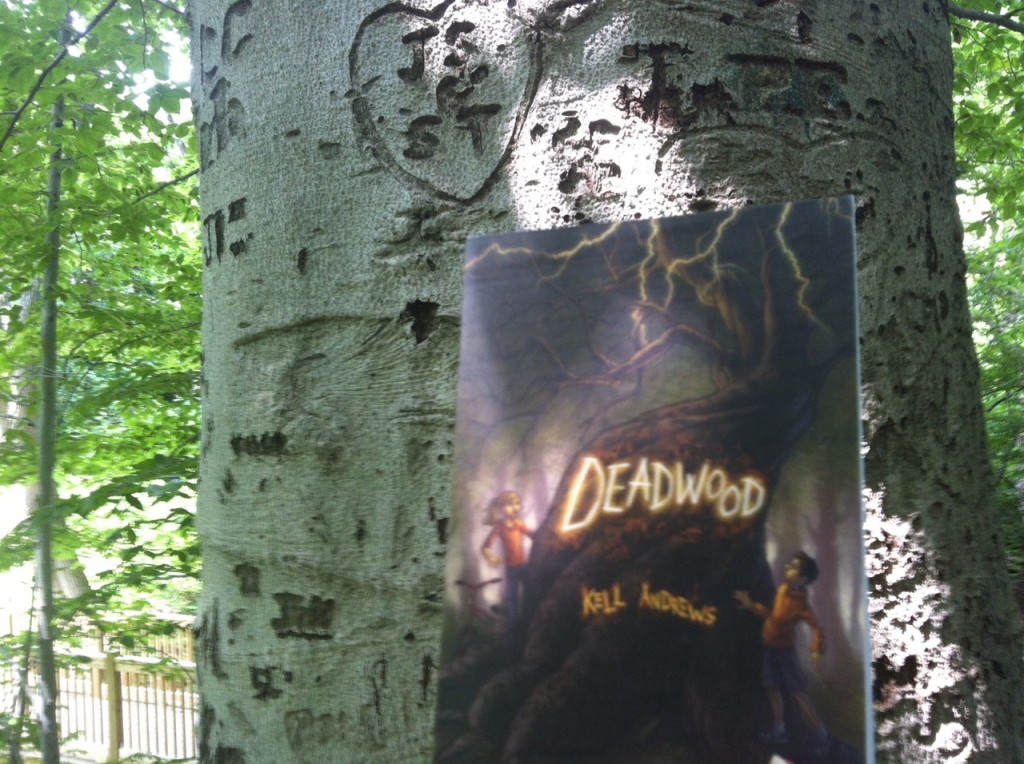

I took my new copy of Deadwood out to the tree that first sparked the idea. It’s a gorgeous old American beech (Fagus grandifolia) in Wynnewood Valley Park, a small wooded park near my home in Lower Merion, PA, that I spotted when I was brainstorming for a new novel idea four years ago. The arborglyphs in the bark were both interesting and disturbing, and I started to wonder what kind of magic they could introduce. That seed of an idea grew into Deadwood.

I took my new copy of Deadwood out to the tree that first sparked the idea. It’s a gorgeous old American beech (Fagus grandifolia) in Wynnewood Valley Park, a small wooded park near my home in Lower Merion, PA, that I spotted when I was brainstorming for a new novel idea four years ago. The arborglyphs in the bark were both interesting and disturbing, and I started to wonder what kind of magic they could introduce. That seed of an idea grew into Deadwood.

Now Deadwood is out as an ebook and paperback from Spencer Hill Press, and the book and the tree have finally met, leaf to leaf.

Read the whole story behind the story >>